Unraveling the Bedrock: The Deterioration of the US Global Currency Reserve System - Part 2

The Erosion of the Petrodollar Framework

As previously mentioned, every global monetary system undergoes a gradual decay, where order gives way to disorder as inherent flaws within the system become evident over time.

In the case of the Bretton Woods system, the flaw emerged as a persistent decline in US gold reserves relative to increasing external liabilities, ultimately leading to an inability to sustain the convertibility of dollars into gold.

For the petrodollar system, the flaw lies in the ongoing trade deficits that the United States must endure with the rest of the world to ensure the global availability of dollars for energy transactions. This reliance on trade imbalances compels the US to outsource significant portions of its industrial sector, resulting in a substantial deficit in its net international investment position as foreign entities progressively own a larger share of US assets.

To put it simply, the flaw in the Bretton Woods system pertained to the United States' capital account, while the flaw in the petrodollar system centers around the United States' current account.

A comprehensive study published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in 2017 titled "Triffin: Dilemma or Myth?" examines the validity of Triffin's dilemma from various perspectives. The paper acknowledges certain aspects of the dilemma while disagreeing with others, and it restates and applies the concept in multiple scenarios. Within this paper, there is a concise summary of the updated concept known as the "current account Triffin dilemma."The most common version of Triffin shifts his thesis from the capital account to the current account. It posits that the reserve currency country must run, or at least does run, persistent current account deficits to provide the rest of the world with reserves denominated in its currency (Zhou (2009), Camdessus and Icard (2011), Paul Volcker in Feldstein (2013), Prasad (2013)). “In doing so, it becomes more indebted to foreigners until the risk-free asset ceases to be risk-free” (Financial Times Lexicon (no date)).

[…]

As applied to the United States, the current account version of Triffin runs as follows. The global accumulation of dollar reserves requires the United States to run a current account deficit. Since desired reserves rise with world nominal GDP, which is growing faster than US nominal GDP, the growth of dollar reserves will raise US external indebtedness unsustainably. Either the United States will not run the current account deficits, leading to an insufficiency of global reserves. Or US indebtedness will rise without limit, undermining the value of the dollar and the reserves denominated in it.

Ultimately, the paper arrives at the following conclusion:While there is much to argue with Triffin and those who invoke his dilemma, there is no arguing the dilemmas posed by a national currency that is used globally as store of value, unit of account and means of payment. “The reserve currency is a global public good, provided by a single country, the US on the basis of domestic needs” (Campanella (2010)). Padoa-Schioppa emphasises the awkwardness of national control from a global perspective. But the global use of the dollar can pose dilemmas to the United States. How should the Federal Reserve respond to instability in the markets for $10.7 trillion in dollar debt of nonbanks outside the United States or in a like amount of forward contracts requiring dollar payments?The central bank ignores such instability at the peril of possible turmoil in US dollar markets that does not stop at the border – even if the floating rate index for dollar debts is brought back from London to New York. Yet the Federal Reserve responds to such instability at the peril of seeming to overreach its mandate.

Issues arising from one country’s supplying most of the world’s reserve currency are not going away.

A Purposeless System

For a period of time, the petrodollar system had a certain degree of logic, despite its flaws in terms of trade imbalances. In the absence of gold backing in the previous system, policymakers managed to establish order in an all-fiat currency system. Given that the United States was the largest economy and the leading importer of commodities, its currency became the most suitable for global oil trade.

Moreover, during the initial two decades of the petrodollar system, which coincided with the Cold War, the system played a role in bolstering US hegemonic power in a divided world. Regardless of personal opinions, the geopolitical intentions of the system's architects were evident.

However, as macro analyst Luke Gromen and others have argued, the system has become less sensible since the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union. It has resulted in increased US military involvement as the United States seeks to defend its role without a clear direction or identity.

Furthermore, China has emerged as the world's largest importer of commodities, surpassing the United States. It becomes challenging to sustain a system where oil and most commodities are priced in US dollars globally when there is a larger global trade partner and importer of these resources. Although the United States retains unmatched military capabilities, its other justifications for the current system are diminishing.Declining US Share of Global GDP

Despite these developments, China cannot replace the United States as the holder of the sole global reserve currency. The gap between them is substantial. No single country possesses the capacity to do so, and here's the reason why.In the aftermath of World War II, the United States accounted for over 40% of global GDP. By the time the Bretton Woods system gave way to the petrodollar system, the United States still represented around 35% of global GDP. However, its share has since declined to only 20-25% of global GDP.And this is based on nominal GDP (i.e., measured in dollars), which is partially influenced by the strength of the dollar. If the dollar were to experience another period of decline, this share could potentially decrease to around 20%. Additionally, when considering purchasing power parity, which better reflects commodity consumption, the United States only represents approximately 15% of global GDP. While this is still significant for a country with 4% of the world's population, it is not sufficient to sustain the petrodollar system indefinitely.

The global energy market, along with international trade at large, has grown too substantial to be primarily priced in the currency of a country with such a small share of global GDP. Imagine if the world attempted to exclusively price energy in Swiss francs; there simply wouldn't be enough of them available for that arrangement to function. While the petrodollar situation is not as extreme, as the United States economy continues to represent a diminishing portion of global GDP, it becomes increasingly challenging for it to supply enough dollars for the world to price all energy transactions in dollars.

No single country or currency group possesses the necessary size and capacity to accomplish this task alone anymore. Neither the United States, China, the European Union, nor Japan can do so.

The United States had a unique ability to fulfill this role for decades following World War II, as many other nations were devastated, and the US held an unusually high share of global GDP. However, as the world expands and becomes more multipolar over time, with no single country dominating global GDP as the United States did in the past, the global monetary system itself requires greater decentralization to function effectively.

We are witnessing the early stages of this transformation.Multi-Currency International Trade

As reported by Bloomberg this year, Russia's exports to China have undergone rapid de-dollarization in recent years, diversifying into a broader range of currencies.Chart Source: BloombergIn the past six years, there has been a significant shift in the currency composition of Russian exports to China. Previously, over 98% of Russian exports to China were denominated in dollars. However, as of early 2020, only 33% of exports are dollar-based, while 50% are based on the euro, and 17% are conducted using Russia's own currency. This shift is particularly noteworthy because a substantial portion of Russian exports consists of energy and commodities, which lie at the core of the petrodollar system.

Similarly, the article highlights that Russian exports to Europe have also become increasingly euro-based. Six years ago, 69% of Russian exports to Europe were priced in dollars, while only 18% were euro-based. However, the current figures indicate a shift, with 44% of exports still dollar-based and 43% euro-based.

Moreover, Bloomberg reported in 2019 that Russia has achieved similar results with India, witnessing a significant decline in the share of exports priced in dollars. Previously, nearly 100% of Russian exports to India were dollar-denominated, but this has dropped to only 20% of exports being priced in dollars.Chart Source: BloombergThis is not the first time an attempt has been made to challenge the existing system. In 2000, Saddam Hussein started selling oil priced in euros, which posed a potential threat to the dominance of the dollar. However, a few years later, the United States invaded Iraq, citing allegations of weapons of mass destruction. These allegations were later found to be false, and Iraq returned to selling oil in dollars.

The extent to which Iraq's decision to sell oil in euros influenced the US decision to go to war is a matter of debate. However, it is worth noting that despite the presence of numerous malevolent dictators around the world, it was the Iraq war that resulted in the loss of 4,500 American lives and the expenditure of $2 trillion in US funds, not to mention the destruction experienced by Iraq.

In 2006, then-Representative Ron Paul delivered a detailed speech to Congress discussing Iraq, the euro, and broader themes related to the petrodollar system and US foreign policy, including policy towards Venezuela and Iran. Regardless of one's stance on Ron Paul as a controversial political figure, his speech holds historical significance and is worth familiarizing oneself with.

However, when major powers like China, Russia, and India begin pricing goods outside of the dollar-based system and utilizing their own currencies for trade, including energy transactions in some cases, the US cannot realistically resort to military intervention. Instead, the US can only exert influence through sanctions, trade disputes, and other forms of geopolitical pressure.

One recent focal point has been the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which runs from Russia to Germany. The US has issued multiple rounds of sanctions and threats against companies involved in the project, as its completion would enhance Russia's gas supply to Europe. Both the executive and legislative branches of the United States have shown great interest in this project. For instance, a group of US senators sent a letter warning of potentially devastating legal and economic sanctions against a German port operator involved in the project. German officials have pushed back, asserting that such sanctions jeopardize European sovereignty.

Another area of contention is the US sanctions against Iran. Europe, India, and China all engage in trade relations with Iran and seek to continue trading with the country. Moreover, all three are major importers of energy, while Iran is an energy producer.

In 2019, Europe established INSTEX, a special purpose vehicle designed to bypass US sanctions on Iran. This mechanism facilitates trade outside of the SWIFT system and the broader dollar system. Although it has been successfully tested, its usage has been limited. Similarly, India has historically maintained constructive trade with Iran, despite religious and cultural differences that often strain relations between India and its neighbor Pakistan, as well as territorial disputes in Kashmir. However, in 2020, the Iran-India trade partnership faced constraints due to a combination of US sanctions and the COVID-19 pandemic. China, too, has numerous strategic energy partnerships and trade agreements with Iran, but both US sanctions and the pandemic have disrupted their trade situation.China's Role in Undermining the Petrodollar System

Over the past seven years, China has been leveraging the petrodollar system to its advantage, working against the interests of the United States. The petrodollar system traditionally encourages mercantilist nations to maintain trade surpluses with the US and reinvest those surplus dollars in US Treasuries. However, China deviated from this pattern by diverting its dollar surplus towards other foreign assets. Experts on petrodollars, such as Luke Gromen, have been reporting on this phenomenon for some time, although it has not received widespread attention.

In the early days of the petrodollar system, Europe and the Middle East were the primary trading partners with the United States, accumulating substantial amounts of dollars that were then reinvested in Treasuries. Japan subsequently emerged as a major trading partner and a global economic center, continuing the trend of running significant trade surpluses with the US and reinvesting in Treasuries. As Japan's growth stagnated and China's influence rose, China became the largest trading partner of the United States, running substantial trade surpluses and also reinvesting in Treasuries.

All seemed well within the petrodollar system, except for those in the US who were concerned about the decline of domestic manufacturing or those affected by military interventions. The wheels of the petrodollar system continued to turn.

However, China disrupted this cycle. In 2013, China declared that it was no longer in its interest to accumulate more US Treasuries, despite continuing to run significant trade surpluses with the United States and receiving dollars. They chose not to recycle those dollars to fund US fiscal deficits by purchasing Treasuries. As stated in the linked Bloomberg article:“It’s no longer in China’s favor to accumulate foreign-exchange reserves,” Yi Gang, a deputy governor at the central bank, said in a speech organized by China Economists 50 Forum at Tsinghua University yesterday. The monetary authority will “basically” end normal intervention in the currency market and broaden the yuan’s daily trading range, Governor Zhou Xiaochuan wrote in an article in a guidebook explaining reforms outlined last week following a Communist Party meeting. Neither Yi nor Zhou gave a timeframe for any changes.

Indeed, China's holdings of US Treasuries have decreased over the past seven years, despite their continued growth in trade surplus with the United States until 2018.

Instead, in 2013, China initiated the Belt and Road initiative. Under this initiative, China aggressively provided dollar-denominated loans for infrastructure projects in developing countries across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Additionally, China offered its expertise in infrastructure development, leveraging it as a technical strength.

Many of these foreign loans, if defaulted on, result in China gaining ownership of the infrastructure itself. Consequently, regardless of the success or failure of the loans, China secures access to commodity deals, trading partners, and tangible assets worldwide.

Below is a map illustrating the global distribution of Chinese funding, and here is a larger view of the map.Chart Source: Visual CapitalistTherefore, the United States currently faces significant trade deficits with other nations, particularly China. However, instead of reinvesting these dollar surpluses into financing US fiscal deficits as in the past, China now utilizes the incoming dollars to fund infrastructure projects globally and expand its global influence.

This situation not only affects blue-collar labor in America but also undermines the geopolitical aspirations of US hegemony. The petrodollar system previously benefited the top half of the income spectrum in the United States, while the bottom half did not experience similar advantages. However, now the system fails to serve both halves effectively. It has lost its purpose.

An insightful quote from Charlie Munger states, "show me the incentives and I'll show you the outcome." While the petrodollar system was cleverly designed in the 1970s, China's subversion of the weakening system is equally clever. The system's inherent flaws make its eventual disruption almost inevitable, as demonstrated by mathematical and Triffin's dilemma.

From a geopolitical perspective, China's motivations are understandable. Western powers inflicted significant damage on China during the Opium Wars in the 1800s, leading to 150 years of Chinese instability and stagnation. Now that China has regained strength and organization, it no longer adheres to the global order established by those Western powers.

Chinese officials have repeatedly expressed concerns about their reliance on the dollar system, considering it a security risk. As China has become the world's largest trading partner and the largest importer of commodities, it has a growing interest in acquiring commodities and engaging in global trade without relying on the dollar. China has taken small steps towards achieving this goal, such as trading with Russia and introducing yuan-based oil futures contracts.

Simultaneously, the United States faces increasing domestic populism, with the persistent trade deficit becoming a pressing political issue that needs to be resolved. Additionally, US officials have highlighted the security risk of depending heavily on critical supplies produced outside the country, particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The trap for US policymakers is attempting to narrow the trade deficit by pushing other countries to buy more American goods. However, this approach is akin to putting a band-aid on a gunshot wound. The underlying problem lies in the structure of the global monetary system itself, which is designed to perpetuate persistent trade deficits in order to distribute dollars worldwide and enforce dollar-only pricing for global energy.

On March 2, 2018, President Trump tweeted that "trade wars are good and easy to win." However, since then, the US trade deficit has increased rather than decreased. Within the current structure of the petrodollar system, trade wars are incredibly challenging for the US to win. While the US may eventually reduce its trade deficit, it would require a fundamental change in the global monetary system.

Therefore, US policymakers find themselves taking military actions or imposing sanctions to defend the dollar's dominance in global energy markets and attempt to address the deepening trade deficit. Paradoxically, the trade deficit is what enables dollars to circulate globally for the purchase of oil or other commodities. This strategy lacks coherence and reflects deep-rooted issues within US political culture rather than being tied to any particular politician.

In the meantime, the entropy of trade deficits gradually erodes the existing system from within, while China exploits the system against its owner. Populism rises in the US and other countries, and Eurasian nations slowly establish non-dollar payment channels, contributing to the ongoing transformation of the global economic landscape.Eating Our Own Cooking

Currently, the US Federal Reserve (represented by the blue line) holds a larger amount of Treasuries compared to the collective holdings of all foreign central banks (represented by the orange line).Chart Source: Bianco ResearchThis is not the intended functioning of a "global reserve" currency. It's comparable to a restaurant chef consuming her own dishes more than her customers do. This is how other non-global reserve countries operate. Within a span of one year, the Federal Reserve has transitioned from owning half the amount of Treasuries compared to foreign central banks combined, to surpassing their combined holdings.

As mentioned earlier, countries can only continue purchasing Treasuries if global dollar liquidity conditions remain favorable. A strong dollar impedes foreign accumulation of Treasuries. Furthermore, any disruptions to trade, such as a pandemic and associated economic shutdowns that severely impact oil demand and import/export volumes, pose a threat to the entire system. Additionally, China has strategic reasons for not recycling dollars into Treasuries.

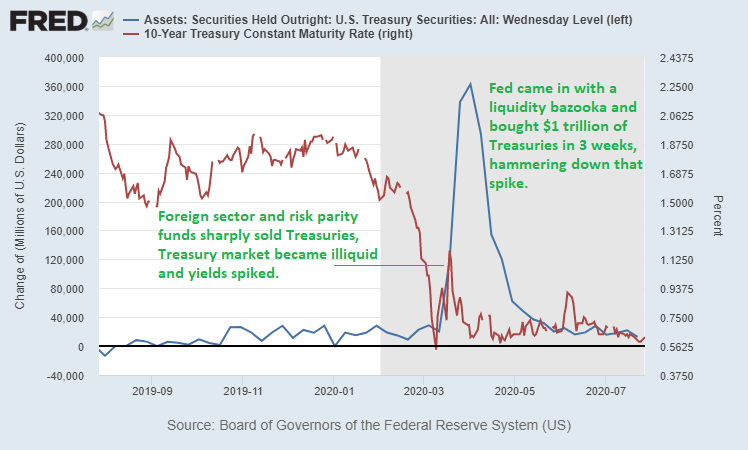

Regarding the Treasury market, in addition to the limited purchase of Treasuries during the past five years of a strong dollar environment, some countries rapidly sold off Treasuries in March and April of this year during the peak of the global shutdown and liquidity crisis. Prior to the pandemic, long-duration Treasuries experienced a rally as investors sought refuge in them, driving their yields down. However, at the height of the liquidity crisis, when the dollar index surged to 103, even Treasuries experienced a significant sell-off.

The Federal Reserve acknowledged this issue during their emergency meetings in March and subsequent meetings in April.

Here's a reference to the events in March:In the Treasury market, following several consecutive days of deteriorating conditions, market participants reported an acute decline in market liquidity. A number of primary dealers found it especially difficult to make markets in off-the-run Treasury securities and reported that this segment of the market had ceased to function effectively. This disruption in intermediation was attributed, in part, to sales of off-the-run Treasury securities and flight-to-quality flows into the most liquid, on-the-run Treasury securities.

Here are two excerpts from April that provide insight into the matter:Treasury markets experienced extreme volatility in mid-March, and market liquidity became substantially impaired as investors sold large volumes of medium- and long-term Treasury securities. Following a period of extraordinarily rapid purchases of Treasury securities and agency MBS by the Federal Reserve, Treasury market liquidity gradually improved through the remainder of the intermeeting period, and Treasury yields became less volatile. Although market depth remained exceptionally low and bid-ask spreads for off-the-run securities and long-term on-the-run securities remained elevated, bid-ask spreads for short-term on-the-run securities fell close to levels seen earlier in the year.

Several participants remarked that a program of ongoing Treasury securities purchases could be used in the future to keep longer-term yields low. A few participants also noted that the balance sheet could be used to reinforce the Committee’s forward guidance regarding the path of the federal funds rate through Federal Reserve purchases of Treasury securities on a scale necessary to keep Treasury yields at short- to medium-term maturities capped at specified levels for a period of time.

And here is the action they took. The red line represents the yields of 10-year Treasuries, while the blue line represents the weekly rate at which the Fed purchased Treasury securities.Chart Source: St. Louis FedMore crucial than the abrupt increase in yields in March was the concerning fact that the Treasury market experienced a lack of liquidity, resulting in wide bid/ask spreads. The market was not functioning properly, and the issue extended beyond the rise in yields.

Since then, the Federal Reserve has gradually scaled back its purchases of Treasury securities from the extreme levels of $75 billion per day. However, they are still buying at a rate comparable to previous instances of quantitative easing (QE), acquiring $80 billion worth of Treasuries each month. In other words, the Fed remains the largest buyer of US fiscal deficits. Although the dollar has weakened from its highs in March, it remains relatively strong historically. Consequently, the foreign sector isn't recycling a significant portion of their dollars into accumulating Treasuries.

This situation arises due to the existence of $13 trillion in dollar-denominated debt worldwide and the substantial demand for dollars, while the supply of dollars is insufficient. As a result, foreign entities begin selling a portion of their $42 trillion worth of dollar-denominated assets to obtain dollars, leading to a crash in US markets and other markets. This compels the Fed to intervene by printing dollars to purchase the assets being sold and establishing dollar swap lines with foreign central banks until sufficient global dollar liquidity is restored.Triffin's Dilemma Unfolds

Ultimately, this raises the question of whether the United States should even strive to maintain the petrodollar system, if it has the option to do otherwise. As demonstrated earlier, the US trade balance is in a state of disarray:Chart Source: Trading EconomicsThe US net international investment position has experienced a significant decline, shifting the country from being the largest creditor nation globally to becoming the largest debtor nation.Chart Source: Ray Dalio, The Changing World OrderThe net international investment position of a country gauges the disparity between the foreign assets it owns and the assets owned by foreigners, as depicted in the provided chart as a percentage of GDP. As of the current year, the United States possesses $29 trillion in foreign assets, while foreigners hold $42 trillion in US assets, encompassing government bonds, corporate bonds, stocks, and real estate.

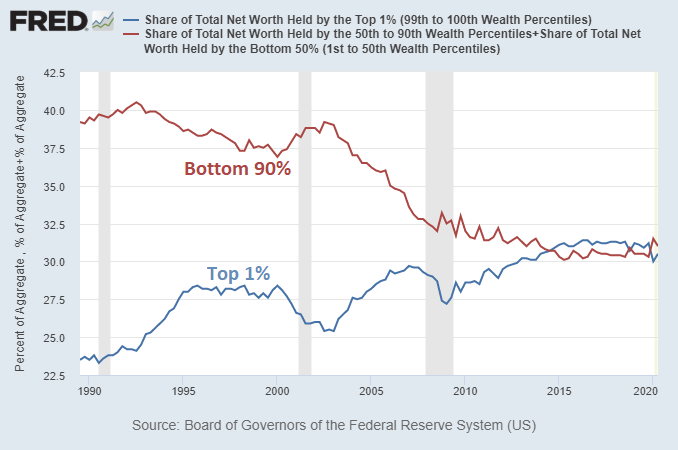

This situation is a consequence of accumulated US trade deficits, coupled with the accumulation of trade surpluses by the foreign sector. Consequently, the US finds itself in one of the weakest positions globally when considering this metric. The data provided reflects the state of affairs as of 2019, and the situation has deteriorated further since then.Data Sources: IMF and various central banksThe level of wealth concentration in the United States has reached a point that surpasses that of nearly every other developed nation.Chart Source: Credit Suisse 2020 Wealth ReportThe wealthiest 1% now possess a comparable amount of wealth as the bottom 90%, reflecting a significantly higher degree of concentration compared to the levels observed 30-40 years ago.Chart Source: St. Louis FedThe United States ranks at #27 globally in terms of social mobility, placing it towards the lower end among developed nations. In the United States, an individual's economic potential throughout their lifetime is significantly influenced by their family's socioeconomic status, more so than in other advanced countries. While there are a few exceptions, we need to look at emerging or developing markets to find social mobility scores lower than those of the United States.

Since the 1970s, median wages in America have become disconnected from productivity, and this disparity has been exploited by individuals at the top due to factors such as offshoring and automation.Chart Source: EPIPresently, the typical American male faces challenges in meeting the expenses associated with supporting a family, which were easily manageable for previous generations. Either an income above the median level or dual incomes have become necessary, as the median income alone no longer provides sufficient support for a family, as it did in the past.Chart Source: Washington Post, Oren CassMeanwhile, there has been a significant and rapid increase in CEO compensation over the past four decades. In 1965, CEOs earned around 20 times more than the average worker, but this ratio escalated to 59 times by 1989, 122 times by 1995, and in recent years, it has consistently exceeded 200 times the earnings of the average worker.

According to the 2019 Credit Suisse Wealth Report, although the United States boasts a high level of wealth per capita, the concentration of this wealth is so pronounced that the median net worth of the average American (representing the 50th percentile or the middle position) is actually lower than that of most other advanced countries. In essence, we have exerted more pressure on our middle and working classes compared to many other nations.Data Source: Credit Suisse 2019 Wealth DatabookIt is not surprising that populism is gaining traction, both from the right and the left, as people sense that something is amiss. However, opinions on the causes and solutions differ among individuals.

Essentially, the petrodollar system and its associated fiscal policies have been gradually unraveling due to inherent flaws that have persisted for decades. This brings us back to the Triffin dilemma, which highlights the need to export an increasing amount of valuable assets, such as gold reserves or industrial base, in order to maintain a global reserve currency. These requirements make such systems long-lasting but not permanent.

Initially, having the global reserve currency confers significant privileges, as the benefits of hegemonic power outweigh the costs of maintaining the system. However, over time, the benefits remain relatively stagnant while the costs compound, eventually surpassing the advantages.

The perception of the value of the system varies depending on whom you ask. Individuals who often occupy higher income brackets and work in finance, government, healthcare, or technology have benefited from this system, gaining the advantages of globalization without experiencing its drawbacks. Conversely, those on the lower end of the income spectrum, particularly those involved in physical labor or manufacturing, have experienced the least benefit and made the greatest sacrifices. Their jobs were outsourced and automated at a faster pace compared to workers in other developed countries. Moreover, even the geopolitical and hegemonic benefits for the political class are being undermined by China's actions, further eroding the system.

As the system weakens, it is easy to attribute its fraying to external nations. When these nations begin pricing goods outside the dollar-based system, employ mercantilist currency policies, construct pipelines, or choose to utilize their dollar surpluses in ways other than reinvesting them in US Treasuries, it may appear as if they are undermining an otherwise sound system.

In reality, these external actions are symptomatic of underlying flaws in the system. Firstly, the United States no longer holds a significant enough share of global GDP to supply an adequate amount of dollars to support global energy markets and trade. Secondly, the US relies on persistent trade deficits to inject dollars into the system. Lastly, an all-fiat global currency system incentivizes many countries to engage in mercantilist currency manipulation to generate trade surpluses against the US whenever possible.The Outlook for the Medium-Term

Looking ahead, regardless of whether significant changes occur to the system or not, the probabilities suggest a weakening of the dollar in the coming years. In other words, there is a likelihood of another downward movement in the value of the dollar, even if the overall structure of the system remains largely unchanged.Chart Source: StockCharts.comThe Comparative Performance of the Dollar and Other Currencies

Some individuals inquire about why the US dollar is more prone to weakening in comparison to other major currencies, even though all of them are engaging in significant monetary expansion. What are the factors behind these substantial bear markets in the dollar?

In simpler terms, even if the US Federal Reserve adopts a dovish stance, implementing quantitative easing (QE) and maintaining zero interest rates, why would the dollar lose strength against the euro, yen, pound, or other currencies that are pursuing similar dovish policies? It is easy to argue that the dollar should weaken against tangible assets (which is likely the more straightforward long-term trade), but why should it also depreciate against other fiat currencies?

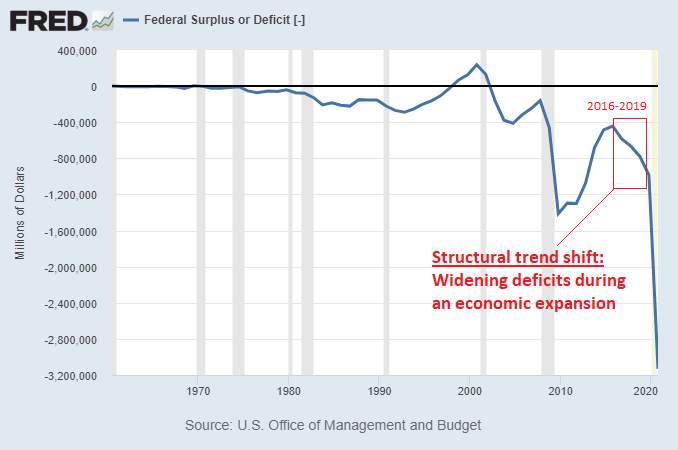

The initial explanation lies in the magnitude of the actions taken. While major countries may be pursuing similar policies, the scale of these measures varies. Prior to the onset of the pandemic, US fiscal deficits as a percentage of GDP were larger than those of most advanced economies, and this trend has continued throughout the pandemic.

To illustrate this point, here is a chart from a November 2020 newsletter illustrating the US federal deficit. It demonstrates that it was the first time in modern history when the United States experienced an increasing deficit (both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP) during the later stages of an economic expansion.Chart Source: St. Louis FedFurthermore, unlike Japan, Europe, and China, which maintain positive trade balances and current accounts, the United States faces the aforementioned Triffin dilemma due to its structural trade and current account deficits. To provide a visual representation, let's look at this chart in 2019 utilizing data from late 2018, revealing that prior to the pandemic, the US possessed the largest twin deficit among major developed nations.Data Source: Trading Economics, various central banksTherefore, when US monetary policy adopts a dovish stance, as it did in 2019, the dollar has significant room for depreciation.

The second explanation lies in valuation. To illustrate this, let's consider the scenario of a value stock with a price-to-earnings ratio of 10x, expected to achieve 5% earnings growth, and a growth stock with a price-to-earnings ratio of 30x, expected to achieve 15% earnings growth. Now, suppose that both stocks fall short of expectations, with the value stock achieving only 4% earnings growth and the growth stock achieving only 7% earnings growth. Due to its higher valuation and the larger relative gap compared to what was priced in, the overvalued growth stock experiences a more significant decline than the value stock.

Similarly, the dollar's strength is bolstered by several factors during a bullish cycle, including offshore dollar-denominated debts, scarcity of dollars outside the United States to service those debts, and a decade of capital inflows into the United States. However, in an environment where all countries, including the US, are injecting massive liquidity and creating more currency units, the specific currency that was overvalued due to scarcity relative to the required demand (the dollar) experiences the most significant depreciation. This is because the scarcity/liquidity issue that was supporting its value is addressed.

Trade deficits indicate an overvalued currency (excessive importing power and uncompetitive export pricing), while trade surpluses indicate an undervalued currency (limited importing power and overly competitive export pricing). Mercantilist countries can manipulate their currency to maintain trade surpluses for a certain period, and the global reserve currency can sustain trade deficits for decades. However, when monetary policy no longer counters these inherent trade forces, exchange rates tend to move towards balanced trade.

During a strong dollar cycle, when the US has a substantial trade deficit and subsequently reduces interest rates and shifts from quantitative tightening to quantitative easing, the dollar has ample room to depreciate compared to the currencies of developed nations that already possess trade surpluses (i.e., undervalued currencies), despite being the global reserve currency. We observed this phenomenon occurring this year, and the question now is whether it will continue.

Furthermore, US stocks are relatively expensive compared to those of many other nations, even after adjusting for sector differences. Therefore, if US equity indices cannot sustain their period of outperformance, capital may begin to flow elsewhere, leading to further currency depreciation.

Typically, due to variations in equity valuations and policy shifts, the region that outperformed in one decade is often not the same region that outperforms in the next decade.Chart Source: iSharesPotential risks to the aforementioned perspective

Over a multi-year timeframe, it is likely that there will be occasional counter-rallies where the dollar demonstrates better performance against other currencies or even outperforms gold, despite being in a declining trend. Therefore, maintaining a clear understanding of the time horizon is crucial.Similar to how the pandemic unexpectedly impacted the view of a weaker dollar in the first half of 2020, there are other tail risks that could temporarily disrupt the outlook. For example, an economic slowdown during the winter before widespread vaccine distribution and changes in consumer behavior, a sovereign debt or banking crisis in Europe focused on southern European countries, a famine in China, or a currency crisis in a major emerging market like Brazil. Additionally, unexpected military engagements between major powers could also have an impact.Any of these outcomes could lead to a temporary surge in the dollar, similar to what occurred in March. While an outlook may be grounded in structural reasons, it still needs to adapt as new data emerges. That's why regular newsletters and research reports are essential, as circumstances can change.In terms of long-term concerns, the eventual issue of southern European sovereign debt should be a source of significant investor apprehension. The euro has its own structural challenges, such as a monetary union without a fiscal union, although that topic warrants a separate discussion. While the euro faces numerous problems, being overvalued is not one of them. During this strong dollar period, Europe has consistently maintained trade and current account surpluses:Chart Source: Trading EconomicsA potential weakening of the dollar against the euro could indeed diminish Europe's trade surplus with the United States. However, it is important to note that a weaker dollar would likely lead to an emerging market boom, which would create additional trading opportunities for European countries in those markets.Long-Term Outlook

As we extend our perspective into the future, we can consider a structural shift away from the petrodollar system itself, rather than viewing it as just another cycle within the existing system.The Gradual Restructuring Scenario

A structural transformation could take place gradually, as it is already happening to some extent. If there is a continuous shift in global trade, particularly in Eurasia, and specifically in the energy and commodities sectors, towards currencies like the euro, yuan, and ruble, and away from the dollar, the international monetary system could become more decentralized over time.

In fact, one could argue that the petrodollar system reached its peak in 2000 and has remained relatively stable over the past two decades, potentially now facing a decline. The following chart illustrates the share of currencies held as central bank reserves:Chart Source: Ray Dalio, The Changing World Order, purple annotations by Lyn AldenAnother perspective is that the petrodollar system reached its peak in 2013 when foreigners held a record high percentage of US debt. During that time, China declared that it was no longer in their interest to continue accumulating Treasury bonds. Since then, the proportion of Treasuries owned by foreign entities has decreased.

As a baseline scenario, I anticipate this gradual trend to persist, regardless of the United States' participation. Major powers are likely to continue increasing their utilization of non-dollar payment systems over time, and a growing portion of US federal debt will be held by the Federal Reserve and the US commercial banking system.

The recently established Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade agreement among numerous Asia Pacific nations, which forms the largest trade bloc in history, could further expedite this trend. Additionally, emerging technologies such as blockchains and domestic government-issued digital currencies present new opportunities for alternative payment networks.The Rapid Restructuring Scenario

On the other hand, a structural change could occur abruptly and in a stepwise manner, similar to the end of the Bretton Woods system. This scenario becomes more likely if the United States actively promotes such a change instead of defending the status quo.

Legislatively, the United States could reverse certain policies outlined in "The Big Tax Shift" to enhance the competitiveness of domestic labor. This may involve measures like reducing payroll taxes or implementing similar actions, as well as reconfiguring spending and taxation priorities to emphasize industrial onshoring to some extent.

On the Treasury and Federal Reserve front, the simplest approach would involve foreign exchange reserves.

Foreign exchange reserves, consisting of foreign currencies in the form of sovereign bonds and gold, are primarily used by countries to manage their currencies. These reserves serve multiple purposes:

Acting as savings, allowing central banks to meet external obligations if necessary.

Enabling central banks to sell foreign exchange reserves and purchase their own currency if their currency weakens, bolstering its value through increased demand.

Empowering central banks to print their own currency and acquire foreign exchange reserves if their currency strengthens excessively, thereby weakening it and increasing reserves for future use.

Since the dollar is the cornerstone of the current global monetary system, US Treasuries constitute a significant portion of most countries' foreign exchange reserves. While the US itself does not hold substantial foreign exchange reserves, emerging markets typically possess the largest reserves due to their greater need, although some developed nations also have substantial reserves. Furthermore, almost every country has a higher percentage of reserves relative to their GDP compared to the United States.

The following chart depicts foreign exchange reserves as a percentage of GDP for various countries as of earlier this year, and the relative magnitudes have remained relatively stable:Data Source: TradingEconomics.com, various central bank websitesIn the case of the United States, the figures mentioned include the official gold reserves at current gold prices, with gold comprising the majority of US reserves.

Regarding Eurozone countries, the European Central Bank holds an additional layer of reserves, in addition to the reserves held by individual countries indicated in the chart. As a result, the numbers presented in the chart for Eurozone countries slightly underestimate the total direct and indirect reserves relative to the euro's GDP.

The United States has the ability to devalue the dollar at any time by printing more currency and using it to purchase foreign assets or gold, thereby increasing its foreign exchange reserves. This approach would align with the strategies of other peer nations. Considering the US nominal GDP surpasses $20 trillion, for every 5% of foreign exchange reserves as a percentage of GDP desired, the United States would need to print and spend over $1 trillion. Consequently, establishing a reserve equivalent to 10% of GDP would require a cost exceeding $2 trillion, particularly as the dollar devalues during the process of building such reserves.

This represents one potential endgame scenario in which the United States could choose to abruptly alter the current structure of the global monetary system. It could decide to transition from being the linchpin of the system to becoming the largest individual player within it by acquiring foreign exchange reserves, devaluing its currency in the process. The US could also adopt various fiscal changes to promote domestic industrial activities, as well as embrace the trend of energy and other commodities being traded in a few major currencies worldwide, rather than solely relying on the dollar.

By pursuing this path, the United States would sacrifice some of its international hegemony in exchange for enhanced industrial competitiveness and greater domestic economic vitality. While the dollar would still remain a reserve currency and the largest individual one, it would no longer hold the exclusive status it currently enjoys.Potential risks to the aforementioned perspective

Significant macro shifts tend to unfold at a slower pace than one might expect based on logical analysis. These types of changes do not occur easily, so it is improbable to accurately predict a sudden and dramatic transformation of the global monetary system in the near future, even though unlikely events can sometimes transpire.

My focus is on monitoring the gradual scenario, observing the ongoing progress or setbacks in non-dollar trade relationships among major powers, particularly concerning energy and other commodities.

For long-term investments, I prefer "win/win" strategies. Currently, scarce assets, especially industrial commodities, are historically undervalued. There are plenty of reasonably priced high-quality stocks available, both within and outside the United States. Additionally, alternative investments such as Bitcoin offer the potential for asymmetric returns, even with small allocations.

Given the stage of the long-term debt cycle we are currently in, some form of currency devaluation is likely to occur during the 2020s, affecting both the US dollar and other currencies. Therefore, holding assets with scarcity value could prove beneficial, regardless of the specific state of the global monetary system at any given time, as determined by policymakers' decisions.